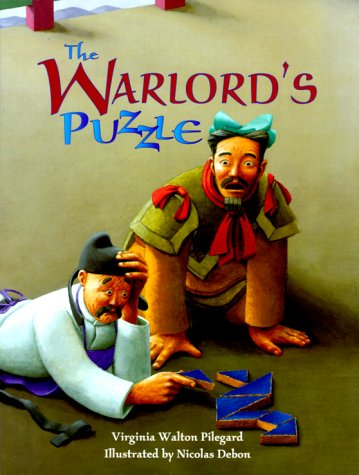

The Warlord’s Puzzle is a children’s picture book that actually grew out of the author’s master’s thesis! Virginia Walton Pilegard was raised on a Nevada cattle ranch, and grew up to be an elementary school teacher – but she wrote her thesis on “strengthening Visual Perception through Informal Geometry.” In “The Warlord’s Puzzle,” she tells a story which teaches presents a challenge using those same informal geometric shapes. And tying it all together, she dedicated the book in part to “all teachers who help students solve life’s puzzles.”

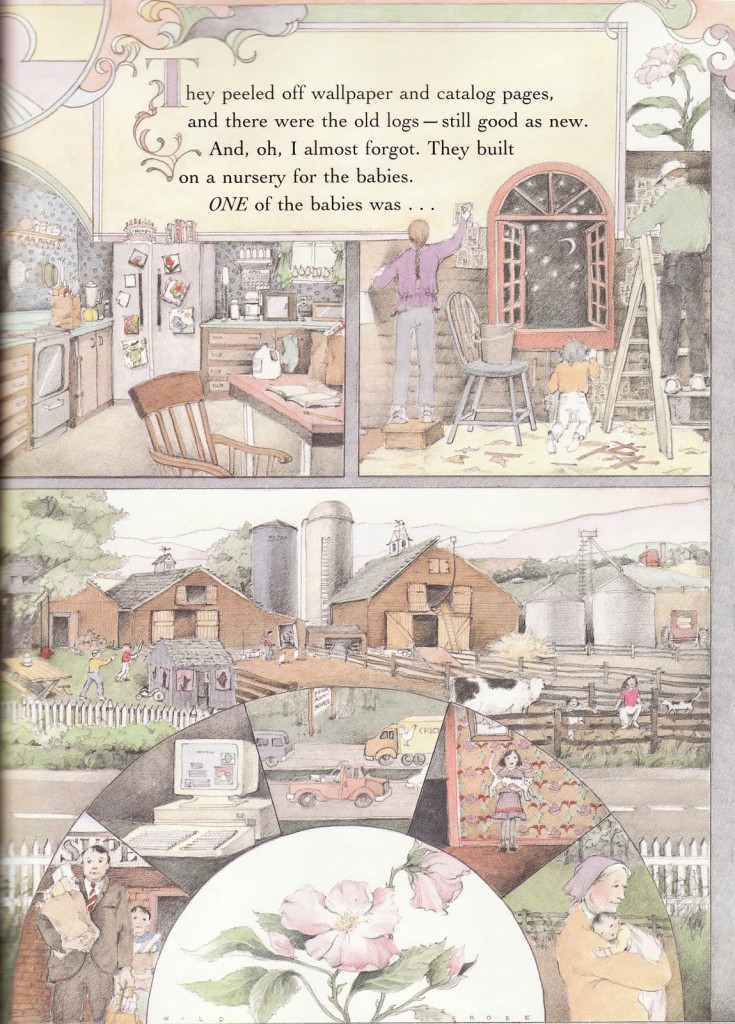

Pilegard’s book tells the story of a fierce Chinese warlord who receives a blue tile as a gift – which is then dropped and shattered into six pieces. She’s establishing the high stakes for solving the geometric puzzle. (Anyone that can reassemble the tile will be given a reward and allowed to live in the warlord’s palace.) Soon there’s a line of people waiting to enter the palace, each hoping for a chance to win the reward. And in a clever twist, the line grows so long that it reaches the fishing hole of a poor peasant and his son.

The poor fisherman becomes a character to root for, since the crowds have frightened away the fish that he’d feed his son for dinner. But the story still seems to drag. There’s the obligatory description of the gold dragons on pillars that are carved inside the palace’s entrance. And then Pilegard suddenly switches characters, to the artist who fears the warlord may punish him for the broken tile. “Master, look at these fine people,” says the artist. “Surely one of them will mend your beautiful gift.”

The characters seem cliche, like the pompous scholar who boasts of his learning, but then isn’t able to solve the puzzle. And there’s something obvious about the implacable warlord, who lacks any personality beyond impatience. But the worst character is the monk, who’s solution is to stack the pieces, then announce “Some riddles are meant to have no answer.” This depiction seems a little unfair to monks – and predictable, the furious warlord vows he’ll also punish both the monk and the scholar.

There’s some cartoon-ish illustrations by Nicolas Debon, but he’s responsible for the book’s greatest oversight. After gushing over the rewards of this tricky geometric puzzle – the reader is never given a chance to solve it themselves until the story is already over. Debon draws it in various states, but it’s meant to remain a mystery until the final page of the book.

Still, it’s satisfying when he draws the fisherman’s son, absently entertaining himself by lifting the blue tile pieces and assembling them into a square.

.jpg)